MANIPULATION OF ANCESTRAL DREAD: NATIVIST RESPONSES TO PERCEIVED FOREIGN HEALTH THREATS

Newly perceived health risks elicit instinctive and protective emotional responses, mostly anguish, fear, and disgust. Their intensity varies based on a person’s previous experiences, available knowledge about the perceived danger, and efforts by politicians and the media designed to validate, exploit, amplify, or distort the menace. Stigmatization and blame seek to ameliorate anxiety by deflecting responsibility to others, notably foreigners. Earlier it was someone from Haiti that supposedly brought HIV/AIDS to America. China was responsible for spreading SARS and the avian flu. More recently, in 2014, a traveler from West Africa introduced Ebola fever. Courtesy of the “girls” and even “boys” from Brazil, dread of another contemporary introduction, the Zika virus, sustains our current national fear mongering.

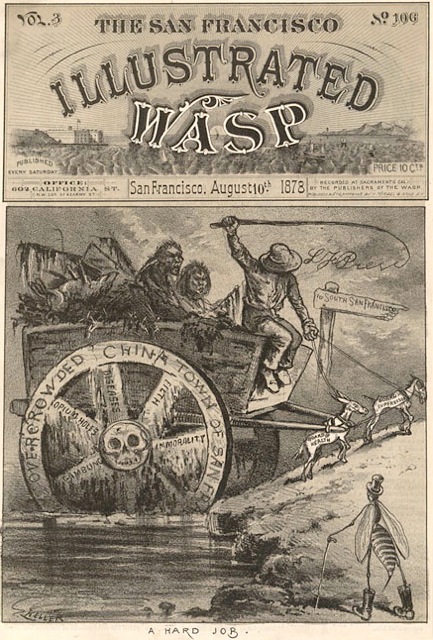

A further historical example is quite illustrative. The bizarre incident involving Charles C. O’Donnell’(1835-1912) and his procession with a Chinese sufferer of leprosy through the streets of San Francisco in the fall of 1878 was recounted elsewhere (Historical News Network, February 1, 2016). It remains a stark example for stirring up strong anti-immigrant feelings through exposure to visibly sick foreign individuals pronounced extremely dangerous to public health. Using terror to mobilize like-minded people and create panic, the macabre parade led to O’Donnell’s arrest at the Palace Hotel. Yet, following his release, the racist doctor turned politician continued to display his xenophobia and obsession with both smallpox and the “scaly disease.” His nativist rants, including the charge that China had already conquered California and its elected officials were receiving their orders from the Emperor in Peking, contributed to the eventual passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Dr. Charles C O'Donnell

Practicing medicine at the edge of Chinatown since the Gold Rush--his office was located on 704 Washington St at the corner with Kearny--O’Donnell boasted to treat families, notably women and children. Originally from Baltimore, his medical credentials remained murky and he often felt professonially threatened, accused of being an abortionist and quack. Undaunted, O’Donnell frequented the streets of the Chinese district, hunting for sufferers of smallpox and especially leprosy “like a hog rooting truffles” as quoted by a New York Times reporter. Detecting and confronting lepers with highly visible lesions, this self proclaimed healer took advantage of their despair and apathy. Pretending to offer a remedy—lumps of pork fat—O’Donnell claimed to “own or seize” his “patients.” Glimpsed from Chinese practitioners, his rationale for employing this popular ethnic food article was supposed to act homeopathically. he blamed those who submitted to his advice for any lack of improvement.

In the summer of 1884 O’Donnell unveiled a new project to spread his fear mongering beyond San Francisco: a trip by train across the country in the company of two Chinese afflicted with advanced symptoms of leprosy. The main purpose was to exhibit them at anti-immigration rallies organized during successive stops in St Louis, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Chicago, New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore, ending in Washington DC. At the nation’s capital, these unfortunate individuals would be brought to the Capitol building and handed over to US Congress members debating immigration legislation.

The ostensible reason for the transcontinental show was O’Donnell’s determination to enlighten East Coast dwellers and authorities about the horrors of foreign leprosy and risks of admitting further “coolies” suffering from despicable diseases. Asked O’Donnell: “Who gave us lepers for our companions, who installed yellow harlots for the avowed purpose of maintaining gambling dens and opium decays?” Public officials, mostly arrogant and ignorant “Eastern monomaniacs” were at fault, allowing Chinese “harbingers of disease and couriers of death” to freely roam the streets of many American cities and towns.

Transportation of diseased Chinese

To achieve his goal, O’Donnell requested a special boxcar to house the sorry victims of this disease, with a partition for an exhibit of photographs taken from other sufferers similarly diagnosed. For him the “heathen Chinee” were like domestic cattle, useful specimens for scientific experimentation and exhibition. However, citing potential risks of contagion and violation of interstate commercial regulations, the railroad companies refused to transport the sick Chinese in spite of repeated threats from the doctor’s rowdy supporters who wished to force the issue by creating a human barrier around the travelers. To avoid further clashes with police, O’Donnell decided in late June to start his sojourn without the company of his “scaly pets,” substituting them with a photographic exhibit described by a local newspaper as “rude portraits of a dozen hideously seamed, scarred and swollen faces.” His departure was celebrated with a spectacular procession through downtown San Francisco to the waterfront before taking the Oakland ferry on it way to the train station. Accompanied by two small German bands, an open hack drawn by four horses carried O’Donnell and to their destination, interrupted by a long-winded diatribe speech promoting the destruction of the infidel Chinese. Another supporter, dressed-up as a medieval crusader, sought to symbolize the religious nature of the racist quest, a clash framed between the Christian cross and a pagan dragon, characterized as a “monster of evil omen” spreading its wings.

The leprosy dragon

Seeking to attract the curious and idle at successive stops along his pilgrimage, O’Donnell extolled his expertise concerning leprosy, always promising to eventually unveil his horrific patients after his lectures. Of course, the sick men never materialized, prompting the doctor to blame the railroad for having delayed the freight car in which his specimens allegedly traveled and then sharing his gruesome photographs with the audience. An editorial in the San Francisco Chronicle asserted: ”Some of Dr. O’Donnell’s talk about leprosy is wild enough to entitle him to a place in a lunatic asylum, while his whole scheme is to secure personal notoriety, not to redress any public evil.”

Arriving in New York City on August 1st, O’Donnell sought lodgings at the Grand Union Hotel. Attracted by newspaper advertisements, nearly 2000 persons congregated at Union Square the next morning, looking for a free show and especially the chance to glimpse the “living dead.” When the prejudiced provocateur announced that the mayor had denied a permit for their display and the freight car in which they lived had been diverted to Brooklyn, the disappointed crowd grew restless. O’Donnell was forced to seek shelter in a nearby tailor’s shop. A week later in Washington DC, a largely Black audience of merely 200 idlers listened impassibly at the steps of City Hall as the high priest of ethnic hate delivered the same racist rant without illustrations. On mayoral orders, no exhibitions or delivery of leprous individuals would be permitted. Undaunted, O’Donnell quietly returned to the West Coast. Perhaps the most bizarre trip in the annals of bigotry sustained by fear of a “loathsome” and incurable disease was over, but its high priest of ethnic hate was rewarded: thanks to voters from wards in white working class neighborhoods and waterfront dwellers, O’Donnell was elected coroner of San Francisco in November 1884. Emboldened, he later ran unsuccessfully as an independent candidate for governor of California and in the 1890s repeatedly for mayor of San Francisco. In his History of the Pacific Coast Metropolis (1912(, John P. Young, the veteran editor of the San Francisco Chronicle, called O’Donnell a “malpractitioner.” A brash medical charlatan and political demagogue, he cunningly exploited contemporary fears about the importation of leprosy to further his racist, anti-immigration stance.

SOURCES:

American Federation of Labor, “Some Reasons for Chinese Exclusion,” reprinted in US Senate Documents of the 37th Congress, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1902

John H. Boalt, “The Chinese Question,” in Chinese Immigration; its Social, Moral, and Political Effects, Report to the California State Senate of its Special Committee on Chinese Immigration, Sacramento: State Office, F. P. Thompson, 1878, pp. 254-6.

Yong Chen, Chinese San Francisco. 1850-1943: A Transpacific Community, Stanford, Cal.: Stanford Univ. Press, 2000.

Noble D. Cook, Born to Die: Disease and the New World Conquest, 1492-1650, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

John Duffy, Epidemics in Colonial America, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971.

Philip J. Ethington, The Public City, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 322-24.

New York Times, Jul 16, 1884, Jul 26, 1884, Jul 29, 1884, August 2, 3, and 9, 1884.

Guenter B. Risse, “Fear of Outsiders is an American Tradition,” History News Network, Feb 1, 2016. http://historynewsnetwork,org/article/161836

Guenter B. Risse, Driven by Fear: Epidemics and Isolation in San Francisco’s ‘House of Pestilence,' Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2016.

Charles E. Rosenberg, The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1845, and 1866, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1962.

San Francisco Bulletin, Jun 30, 1884.

San Francisco Call, Jul 20, 1884.

San Francisco Chronicle, Jul 19, 1884, Aug 4, 1884.

Nayan Shah, Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Peter N. Stearns, American Fear: The Causes and Consequences of High Anxiety, New York: Routledge, 2006.

John P. Young, San Francisco: A History of the Pacific Coast Metropolis, San Francisco: S.J. Clarke Publ. Co, 1912.