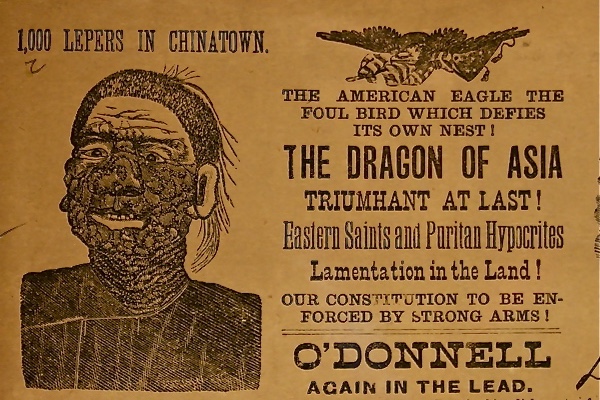

As described in my recent book Plague, Fear and Politics in San Francisco’s Chinatown, (Johns Hopkins, 2012), one of William R. Hearst's newspapers, the New York Journal, issued a special Sunday “Plague Edition,” leading with a headline that announced “The Black Plague Creeps into America.” The accompanying news story painted a sensational scene of the purported epidemic with men collecting bodies of plague victims in the streets of Chinatown. These fictitious accounts, based on biblical and historical descriptions and medieval iconography, painted a picture of dread and panic among San Franciscans. Even interviews with Chinese residents uncovered “much fear.” Some of these feelings were directed at American physicians said to poison their children. No one played in the streets; mothers were afraid of leaving their homes since “doctors are going to send all Chinese away far out to sea on rock; no room. no place. Chinese must all leave Chinatown.” There was also fear of “Mexican” soldiers invading the district and forcing all inhabitants to be inoculated with deadly poison.

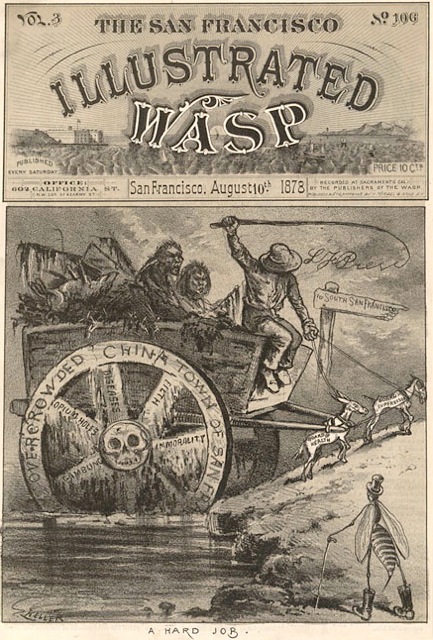

Today, globalization and the formation of pluralistic societies seem to enhance feelings of aversion directed at virtually all aspects of human relationships: we are said to be a fear and disgust-obsessed species. Deviance is a social construction employed to define, separate, and marginalize certain categories of individuals or groups believed to threaten the order, morality, and conformity of an established majority, including those supporting public health and safety. As my new book Driven By Fear: Epidemics and Isolation in San Francisco’s ‘House of Pestilence’ makes clear, a highly charged rhetoric frequently employs emotional imagery and language to assert cultural superiority and achieve social separation. Under such circumstances, dread and revulsion help develop prejudice and stereotyping, especially around issues of morality, ethnicity and nationality—but also with regard to religious beliefs, gender roles, and bouts of sickness.

Since its inception, people in the United States have displayed a singular emotional style: constant fear of contracting diseases brought to its shores by immigrants coming from all over the world. According to the modern Western sanitary gospel, the newly arrived “unwashed” were expected to adopt hygienic values on their road to assimilation and eventual citizenship. In fact, dread has recently been called “one of the dominant emotions in contemporary American public life.” By the end of the summer 2009, as fears of a lethal and catastrophic pandemic of H1N1 influenza outbreak escalated, Fox News aired a television segment with flashing signs of “Mass Quarantines” and a repetitive sound track declaring “Be Very Afraid.” Similar warnings were expressed during the 2003 worldwide SARS outbreak.

Last spring, residents in a small Southern California town angrily protested the illegal arrival of refugees--notably children from Central America. Amid howls of “invasion” and references to other calamities, the question “what happens when they come here with diseases?” revealed this deeply imbedded cultural fear. In fact, replaying a sequence of events linked to the 1900 outbreak of bubonic plague in San Francisco, several US cities near the border with Mexico passed resolutions banning illegal aliens “suffering from diseases endemic in their countries of origin” from their communities.

Ebola’s association with the poverty, filth, and backwardness of underdeveloped Africa, similarly offends the eye and generates widespread dread and repugnance. These anxieties are compounded by the disease’s horrific terminal bodily disintegration, including the messy discharge of bodily fluids. Given Ebola’s lethality, and with no obvious cure or vaccine as yet available to protect sufferers, a revolting foreign invader threatened last summer to slip across America’s borders and cause mayhem. Fear mongering thus became ubiquitous; rumors, print media, and an ever-expanding Internet succeeded in transforming the presence of a few cases of an exotic killer in the homeland not only into an urgent national problem but also an international security crisis.

With barely disguised racial, class, and ethnic overtones, the “pandemic fear” reached nearly apocalyptic levels in mid October 2014 when two hospital nurses caring for the dying Liberian patient also contracted the highly lethal scourge. The reaction was immediate: ”letting the unknown into the country” was totally unacceptable. Perhaps all Ebola suspects should be placed on offshore hospital ships. Moreover, a relentless media blitz went viral, distorting the scientific information concerning the true risks posed by the disease. In word and image, America’s journalists magnified the danger, creating a veritable panic widely characterized as “hysteria.” With Its proximity to Halloween, the drama seamlessly melded Ebola fright with entertainment. Trick or treat revelers featured beaked medieval plague doctors and space-suited—hazmat--health workers. Freaked out by the threats, “who could blame you for deciding to remain indoors, alone in bed, indefinitely,” caustically observed one New York Times columnist.

Humans have always framed their reaction to the presence of disease by employing military metaphors. Because mass disease posed an existential risk, forceful, coercive responses powered by aversive emotions employed police or military force. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, quarantine and isolation are still considered effective “police power” functions designed “to protect the public by preventing exposure to infected persons or to persons who may be infected. In emergencies, the Department of Defense plays an important role in mobilizing troops while state, local, and tribal law continues to guide the implementation of similar protective measures to control the spread of infectious disease within their borders. After the Ebola outbreak, a presidential executive order urged the Defense Department to prepare for a call up of reservists from the National Guard, and set up a rapid reaction squad. The so-called “Ebola SWAT team” was envisioned as a specialized group of experts in logistics, epidemiology, medicine, and specialized caregiving, assembled by the CDC and ready for deployment anywhere in the US to assist local authorities and healthcare systems in safety and infection control.

Near panic, a majority of the public demanded a more muscular response. A national poll suggested that over 80% of the population favored stringent measures to deal with the Ebola outbreak. Several governors--some engulfed in reelection campaigns—obliged “out of an abundance of caution,” ordering strict and mandatory 21-day home quarantines. The seclusion targeted all health care workers returning from West Africa after an emotionally draining tour of duty attending Ebola patients. Tracked by police, the potentially infected were to monitor their temperature but were not allowed to contact family members or receive visitors. “You can’t take chances on this stuff,” commented the New Jersey’s governor, in reference to an arriving nurse who despite negative tests and lack of symptoms was summarily confined.

Yet, suspicion and apprehension about militarized federal interventions linger, notably in an American culture proud of its organizational prowess and “can do” resolve. Detention can often be counterproductive; violations of human dignity humiliating and degrading since they frequently tend to encourage resistance and evasion. Like their predecessors centuries ago, contemporary public health authorities dealing with Ebola admitted that aggressive monitoring and watching can trigger “perverse incentives” to evade the quarantine. Historically, suspects or sufferers of particularly “loathsome” diseases were expected to cope and adjust to their stigmatized status as pariahs. Medieval castaways were forced to dispose of their properties and leave homes and communities. Shamefully concealing their disgusting appearances, suspects and sufferers were often forced to abandon occupations, break up relationships, seek admission to special institutions, or simply go into hiding. Yet coercion always compromises human dignity, a complex religious and secular concept closely linked to identity and social status. For many in America, the crass inhumanity of such an exile was obvious.

With the advent of civil rights, so-called “social distancing” in private homes or hospital isolation are now seldom involuntary. Yet, the psychological effects of strict social isolation can be serious. Anxiety and fear of contagion--even the possibility of death--could leave many suspects traumatized, lonely, and depressed. In SARS, some observers claimed that, following their ordeal, quarantined persons suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. In the Ebola crisis, Kaci Hickox, the nurse in New Jersey, found her experience “painful and emotionally draining.” After a tough tour of duty in Africa attending the sick and dying, she was isolated across from a Newark hospital in a drafty tent equipped with a potable toilet. Deprived of her clothing and outfitted with skimpy paper scrubs, the involuntary patient rightly questioned the inhumanity of her virtual imprisonment. Appalled, she was quoted as saying “I don’t plan on sticking to the guidelines” before seeking legal recourse, a rebellion that galvanized the country and led to her eventual discharge, thus illustrating the deeply emotional plight of those subjected to quarantine. Every unwarranted abuse of power can easily heighten and spread the very fear it was meant to suppress. While emotions will always dominate the advent of mass sickness, we must be aware of their influence and power in shaping our behavior and therefore seek to moderate all responses towards a fair way to not only protect the public health but also the suspected or sick victims of disease.

SOURCES

Guenter B. Risse, Plague, Fear and Politics in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012.

Rick Gladstone, “Liberian Leader Concedes Errors in Response to Ebola,” NY Times, Mar 12, 2015.

Peter N. Stearns, American Fear: The Causes and Consequences of High Anxiety, New York: Routledge, 2006.

Paul Rozin, Jonathan Haidt and Clark R. McCauley, “Disgust,” in Handbook of Emotions, ed. M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, and L. Feldman Barrett, New York: Guildford Press, 2008, pp. 757-76.

William I. Miller, The Anatomy of Disgust, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997.

David Gentilcore, “The Fear of Disease and the Disease of Fear,” in Fear in Early Modern Society, ed. William G. Naphy and Penny Roberts, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1997, pp. 184-208.

Guenter B. Risse, “Epidemics and History: Ecological Perspectives and Social Responses, in AIDS: The Burdens of History, eds. E. Fee and D. Fox, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988, pp. 33-66.

Guenter B. Risse, Driven by Fear: Epidemics and Isolation in San Francisco’s ‘House of Pestilence,’ Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press (in press)

Cassandra White, “Leprosy and Stigma in the Context of International Migration,” Leprosy Review 82 (2011): 147-54.

Judith W. Leavitt, “Public Resistance or Cooperation: A Tale of Smallpox in Two Cities,” Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice and Science 1(2003): 185-92.

George J. Annas, “Pandemic Fear,” in Worst Case Bioethics: Death, Disaster, and Public Health, New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Lawrence Downes, “When Demagogues Play the Leprosy Card, Watch Out,” NY Times, Jun 17, 2007.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Legal Authorities for Isolation and Quarantine, http://www.cdc.gov/quarantine

Jeffrey M. Drazen et al., “Ebola and Quarantine,” New England Journal of Medicine--on line--(Oct 27, 2014)

Noam N. Levey and Kathleen Hennessey, “Obama Tells CDC He Wants Ebola SWAT Team Ready to Go,” NY Times, Oct 15, 2014.

Interview with Kaci Hickox, Dallas Morning News, Oct 25, 2014.

Karin Huster, “Don’t Let Fear Drive Response,” The Seattle Times, Nov 2, 2014.